Issue #72- November 2021

Welcome to Focus on Fatigue!

It’s that time of year again! Some of us are springing forward, some of us are falling back and some are staying where they are! And it’s all thanks to daylight saving!

Some people love it. Some people hate it. But we are all affected by it in some way, even if we don’t live in a place that observes daylight saving time.

In this month’s Focus on Fatigue, we will look at the ‘why?’ and the impact of all this strange time changing.

The FRMS Team

![]()

Views expressed in articles and links provided are those of the individual authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of InterDynamics (except where directly attributed).

Daylight saving

Why do we do it? And what’s the impact?

What’s the point?

What’s the point?

The main purpose of daylight saving time, (did you know it is daylight saving not daylight savings?) is to make better use of daylight. We change our clocks during the summer months to move an hour of daylight from the morning to the evening. This allows people to take advantage of light and warmth and participate in evening activity. However, originally the motivation for daylight saving was to save on the use and cost of artificial light.

History of daylight saving

Some people credit Ben Franklin with the invention of daylight saving, which is a bit of a stretch. However, he did write a satirical piece for the Journal de Paris in 1784, suggesting Parisians change their sleep schedules to save money on candles and lamp oil.

Daylight saving was first proposed in earnest by George Hudson in New Zealand in 1895. However, residents of Port Arthur, Ontario (now Thunder Bay) were the first to adopt a period of daylight saving time in 1908, followed by some other locations in Canada. Germany was then the first country to implement daylight saving, in 1916 during World War I, to minimize the use of artificial light to save fuel for the war effort. UK, France and other countries followed suit shortly after, with Australia and Newfoundland adopting daylight saving in 1917 and the U.S. in 1918. Many reverted back to standard time after the war. Since then, it has been adopted on and off in various places for different periods.

Current situation

Approximately 70 countries currently utilise daylight saving time (DST), or summer time, in at least part of the country. Countries near the equator are less likely to observe daylight saving. They have less need for it due to the warmer climate and more consistent daylight hours throughout the year. Even within countries that do observe daylight saving, it is often not adopted by all states and territories.

While the savings on energy may have originally been a valid justification, this advantage no longer stacks up. Our energy use has changed (more energy-efficient lighting, more electrical gadgets and energy sucking air conditioners), negating, or reversing, the energy saving benefit in some instances.

Divided opinions

Daylight saving remains an issue of contention in many places. It continues to be a topic of debate in Europe and America, with future changes likely. Some are pushing to abolish daylight saving time, while others are pushing to adopt daylight saving time all year round.

Challenges

Daylight saving is problematic for farmers, who have lobbied against it from the beginning. It disrupts their schedules, particularly dairy farmers, and leaves less morning sunlight to get crops to market.

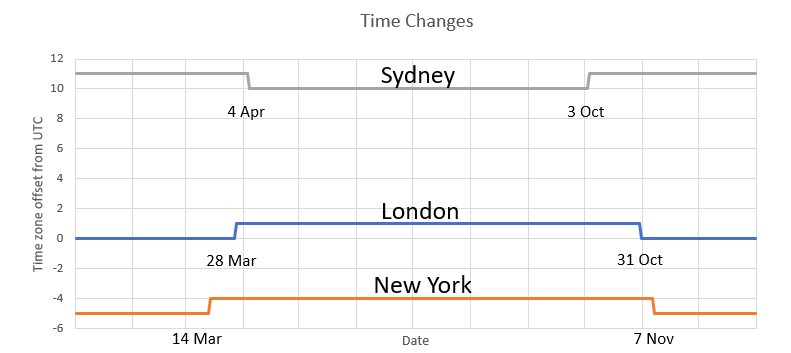

When it comes to conducting global business, constantly changing time zones also present challenges, and not all countries start/end daylight saving at the same time. This means the time difference between two locations can change four times in a year and the situation becomes further complicated when scheduling across multiple locations.

A number of studies have shown negative impacts relating to daylight saving. Most of these relate to the period immediately after the time change, resulting from disruption to circadian rhythm and sleep. Research suggests that the shift to daylight saving raises the instance of heart attack and other cardiac events. A study out of the US found a jump in fatal car crashes in the days following the shift to DST. And another study identified an increase in workplace injuries immediately following the switch to DST.

So, what’s the upside?

Along with those who enjoy the longer summer evenings, there are other benefits too. The extended evening light may result in an increase in physical activity in children and a decrease in robberies. Studies also found that it may result in fewer wildlife killed by vehicles and less road incidents.

Tips to adjust

For those who do have to go through the transition to and from daylight saving time, keep in mind these tips:

- Start to slowly adjust your body clock in the few days leading up to the start of daylight saving by waking up a little earlier each day.

- Eat a healthy breakfast first thing in the morning.

- Spend time outdoors. Go for a walk in natural light.

- With children, adjust slowly by putting children to bed a little earlier each day in the few days before the change, and reverse the process at the end of daylight saving.

Research

- Barnes, C. & Wagner, D. (2009) Changing to daylight saving time cuts into sleep and increases workplace injuries. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1305–1317. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015320

- Buckle, A. (n.d.) History of Daylight Saving Time (DST). Time and Date. https://www.timeanddate.com/time/dst/history.html (Accessed 20/10/2021)

- Chudow, J. Dreyfus, I. et al (2020) Changes in atrial fibrillation admissions following daylight saving time transitions, Sleep Medicine, 69, 155-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.01.018

- Doleac, J. & Sanders, N. (2015) Under the Cover of Darkness: How Ambient Light Influences Criminal Activity. The Review of Economics and Statistics 97(5), 1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00547

- Ellis, A. et al. (2016) Daylight saving time can decrease the frequency of wildlife-vehicle collisions. Biology Letters, 12. http://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0632

- Ferguson, S., Preusser, D., Lund, A., Zador, P. & Ulmer, R. Daylight saving time and motor vehicle crashes: the reduction in pedestrian and vehicle occupant fatalities

- Fritz, J., VoPham, T., Wright, K. & Vetter, C. (2020) A Chronobiological Evaluation of the Acute Effects of Daylight Saving Time on Traffic Accident Risk. Current Biology 30(4), 729-735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.045

- Goodman, A., Page, A. & Cooper, A. (2014) Daylight saving time as a potential public health intervention: an observational study of evening daylight and objectively-measured physical activity among 23,000 children from 9 countries, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-11-84

- Guven, C., Yuan, H., Zhang, Q., & Aksakalli, V. (2021) When does daylight saving time save electricity? Weather and air-conditioning. Energy Economics, 98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105216

- Jiddou, M. R., Pica, M., Boura, J., Qu, L., & Franklin, B. A. (2013) Incidence of myocardial infarction with shifts to and from daylight savings time. The American journal of cardiology, 111(5), 631–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.11.010

- Kantermann, T., Juda, M., Merrow, M. & Roenneberg, T. (2007) The Human Circadian Clock’s Seasonal Adjustment is Disrupted by Daylight Saving Time. Current Biology, 17(22), 1996-2000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.025

- Kotchen, M. & Grant, L. (2008) Does Daylight Saving Time Save Energy? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Indiana. NBER. https://doi.org/10.3386/w14429

- Küfeoğlu, S., Üçler, S., Eskicioğlu, F., Öztürk, B. & Chen, H. (2021) Daylight Saving Time policy and energy consumption, Energy Reports, 7, 5013-5025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.08.025

- Pacheco, D. (2020) Daylight Saving Time. Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/circadian-rhythm/daylight-saving-time (Accessed 20/10/2021)

In The News

Provided below are a selection of articles from around the web on the issues associated with fatigue. We hope you find them useful and interesting.

Related Articles

Daylight Saving Time Explained

CGP Grey, You Tube, October 2011

Every year some countries move their clocks forward in the spring, only to move them back in the autumn. To the vast majority of the world who doesn’t participate in this odd clock fiddling, it seems a baffling thing to do. So what’s the reason behind it?

Should we abolish daylight saving time – or apply it across Australia?

Nick Evershed, The Guardian, October 2021

These interactive graphics use sun position calculations to show how daylight saving affects daylight hours, and the effect of any changes

Study analyzes the potential consequences of canceling daylight saving time

Emily Henderson, News Medical, October 2021

A study by José María Martín-Olalla of the University of Seville has analyzed retrospectively and from a physiological perspective the potential consequences of canceling daylight saving time, the biannual change of clocks. In his conclusions, he argues that maintaining the same time during all twelve months could lead to an increase in human activity during the early morning in the winter months, with the potential repercussions on human health that this would entail.

Recent Studies Relating to Sleep and Fatigue

Meeting sleep recommendations could lead to smarter snacking

Ohio State University, Science Daily, September 2021

Missing out on the recommended seven or more hours of sleep per night could lead to more opportunities to make poorer snacking choices than those made by people who meet shut-eye guidelines, a new study suggests.

NASA Lab Studies Sleepiness and Use of Automated Systems

Abby Tabor, NASA’s Ames Research Center, September 2021

Drowsy driving accounts for a large proportion of car crashes, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. So, you might think self-driving cars would fix that. After all, computers just don’t get sleepy. But today’s vehicles are only partially automated, requiring the human driver to stay alert, monitor the road, and take over at a moment’s notice. A new study conducted by the Fatigue Countermeasures Lab at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley suggests this passive role can leave drivers more susceptible to sleepiness – especially when they’re sleep deprived.